How you can use daily time card data to check staffing levels at almost every U.S. nursing home

Decades of academic and federal research has consistently proven that the staffing levels of nurses and aides affects the quality of care received by residents of skilled nursing facilities, often known as nursing homes.

Yet, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which regulates the industry, has never set numeric staffing minimums for care hours per resident. While 35 states have their own minimum staffing laws, none meet the levels recommended by experts decades ago as the low bar for avoiding medical errors and delayed care. Most stays in nursing homes are paid for by two federal insurance programs, Medicaid or Medicare, totaling nearly $100 billion each year.

In September 2023, President Joe Biden’s administration revealed the first proposal for nationwide numeric guidelines. Public comment is being accepted through Nov. 6 via the Federal Register, where reporters can find a variety of arguments from stakeholders about whether the reform would do enough or be effective at all.

The federal proposal sets levels lower than a landmark 2001 CMS study, even though the health conditions of nursing home residents have become more complicated. For many residents, providing adequate care would likely require more care from nurses and aides than the minimum identified in that study: 4.1 hours per day.

Over the first 90 days of 2023, fewer than 150 of the nation’s nearly 15,000 skilled nursing facilities – less than 1% – met two core standards of the draft rule, according to a USA TODAY analysis by reporter Jayme Fraser. Read that story and view the interactive map of facilities here and here.

This reporting recipe will provide suggestions on how to use that daily time card data to report about facilities in your local community or state.

Why write about staffing levels at nursing homes?

Staffing levels lower than research-backed minimums are very common. It matters because lives and livelihoods are at stake. This journal article provides a broad research overview of potential consequences of understaffing and other related causes of poor care.

One day, low staffing might result in a delayed diaper change or missed shower. That is a violation of federal law requiring “dignity” for nursing home residents and could have more significant health consequences for people with certain conditions.

Tracey Pompey, a Virginia advocate for residents and former certified nursing assistant, said people who are older or have disabilities that require skilled nursing care – for weeks or for years – often are ignored by society.

“People get desensitized to things like this,” she told USA TODAY. “If it happens to a child or a dog, people won’t shut up.”

Consider low staffing a game of chance with potentially serious consequences.

One day, low staffing might result in a delayed diaper change or missed shower. That is a violation of federal law requiring “dignity” for nursing home residents and could have more significant health consequences for people with certain conditions.

But another day, low staffing could mean hours until a fall, stroke or serious change in condition is noticed and treated. Virginia inspectors documented such delays in the death of Pompey’s father, although the understaffed facility did not face a fine for it.

Nurses and aides (and facility operators) cannot predict which day will be which. They do frequently document the consequences when a resident goes days, weeks or months without appropriate care. Omitted care that seems minor in isolation can compound into serious issues.

For instance, it is common for aides and nurses to skip helping people out of bed when they are too busy to do so or to properly supervise them. Spending days in bed can lead to declines in health and, in the case of serious pressure ulcers, can be fatal. If people cannot rely on aides to help them leave bed, they sometimes try to do so on their own, leading to falls, broken bones and concussions.

Low staffing has significant consequences for health care workers, too.

Homes serving communities of color and rural areas often rely disproportionately on payments from Medicaid, which pays less than Medicare, so those facilities could be particularly vulnerable to increased costs if the staffing regulations are not paired with increased reimbursement rates funded by U.S. Congress

Nurses and aides caring for too many residents report cutting corners. They burn out from impossible demands and don’t feel that they’re living up to their mission to care for people. That fuels frequent turnover and a loss of expertise in skills as well as familiarity with residents. The resulting work culture in some nursing homes is one where leaders struggle to retain good workers and feel pressured to keep underperforming employees just to have bodies in the building. Workers say improved staffing levels would make them more likely to continue working in nursing homes rather than leaving the sector.

For operators of nursing homes, staffing is the highest business cost so mandatory minimums will affect budgets.

The proposed rule would require most facilities in the U.S. to hire more direct care workers or reduce the number of residents it serves with the existing staff. Some businesses might shift some duties between workers, cutting LPN positions without a minimum staffing requirement to offset the cost of hiring more RNs and aides as would be required. And since the industry already pays lower wages than other health care settings and the nation faces a significant shortage of healthcare workers, increasing staffing levels will be difficult.

The industry’s trade association and other groups argue the rules could result in some facilities closing as profit margins shrink. Homes serving communities of color and rural areas often rely disproportionately on payments from Medicaid, which pays less than Medicare, so those facilities could be particularly vulnerable to increased costs if the staffing regulations are not paired with increased reimbursement rates funded by U.S. Congress.

Academics say that annual financial reports submitted by nursing homes to CMS do not accurately reflect the dollars at play. While the business operating the facility with payments from federal coffers may appear to be losing money, lawsuits have frequently revealed that the web of companies that own that business or the building itself are profitable.

Who does what in a nursing home?

Let’s review key players in a nursing home that you’ll need to know. Experts typically talk about three roles when it comes to staffing minimums:

-

Registered Nurses (RNs) write individual care plans, monitor changes in condition and write orders for treatment carried out by other licensed nurses and aides. They are the most extensively trained, typically spending two to four years on coursework and hands-on learning before taking a licensing exam.

-

Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs or LVNs) deliver medical care and tests as ordered by registered nurses, including dispensing oral medications. The scope of duties allowed varies significantly between states. Training programs typically take one to two years to complete.

-

Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs or aides) spend the most time with residents of any staff member. They assist residents with “activities of daily living” such as toileting, bathing, eating and help getting out of bed. Training programs last one to four months and sometimes can be completed on site at a nursing home.

Other people in the facility to know:

-

Operator refers to the company or nonprofit that hires nursing staff, provides care and bills CMS for that care. Sometimes these are small, family-run businesses with one facility or a regional chain. About one of every five nursing homes in the U.S. is owned by one of the 10 largest chains, such as Genesis HealthCare, Life Care Centers of America, Ensign and HCR ManorCare. Most of those are for-profit corporations.

-

Related Party is the official term for a company that provides services to a nursing home or its operator but is not the operator –meaning they do not employ the registered nurses. For example, it is common for operators to pay a different company to manage its onsite pharmacy or provide physical therapy services to residents. Sometimes these companies oversee food services, laundry or cleaning. In some cases, these companies share a corporate owner with the operating company or have other business ties.

-

There is not an official term for this, but many nursing home operators do not own their buildings. Instead, they pay rent to a landlord, often a corporate entity that includes guaranteed rent increases in its contracts or treats the real estate as an investment. Some operators prefer this arrangement so they do not have to manage facility maintenance.

-

An Administrator is the person who runs an individual nursing home and is responsible for meeting federal regulations. This manager reports to the operator, might coordinate payments to the landlord, must respond to any problems cited by inspectors and oversees all the care staff at a facility. They are typically licensed by a state board.

-

Each facility will have at least one doctor or nurse practitioner (NP) who decides on treatment plans for residents and coordinates with the Director of Nursing to tweak those plans based on conditions observed by RNs. Physicians and NPs are not required to be on site and usually an operator will have one person serve many facilities.

-

Ombudsmen are state or county employees who serve as advocates for residents and their families, helping to resolve disputes and guiding people through the complicated systems of senior care. One resident advocacy group, National Consumer Voice, provides information for contacting the ombudsman programs in each state.

-

Surveyor is the formal term for an inspector. Except for occasional federal programs of limited scope, most facilities are reviewed for compliance with federal regulations by state survey agencies (SSAs). When survey teams visit a facility and find a violation of a federal rule, their inspection report will note a “deficiency” and give it a “scope and severity” rating to signify how serious the issue is and how many people are affected. Learn more about that rating system and the range of actions CMS can take against a nursing home for deficiencies on this website.

What are appropriate staffing levels?

Research has consistently correlated the quality of care with the level of staffing, but quantifying how much care is needed, exactly, is complicated.

CMS scores facilities on a variety of quality outcomes and metrics to generate the grades presented by the federal Nursing Home Care Compare website. You can find details about the Five-Star Quality Rating System at this site and a short overview in this story.

It is important to note that parts of the federal rankings result from comparisons to other nursing homes, not from comparisons to best practices. One of the factors used in scoring is staffing levels compared to what a Medicare payment formula predicts is necessary based on each resident’s medical profile. (USA TODAY’s investigation documented how that standard is conservative and often falls short of other recommendations.)

Currently, federal rules do not specify how much bedside care should be provided, saying only that there should be “sufficient nursing staff,” a licensed nurse (such as an LPN or RN) on duty at all times and a registered nurse providing care at least eight hours each day.

Under the current proposal, the sufficient staffing requirement would continue but facilities would need to have a registered nurse on site 24/7. Among other changes, the proposal would require facilities to ensure RNs provide a daily average of at least 0.55 hours of care to each resident and that CNAs provide a daily average of at least 2.45 hours of care to each resident.

They would set minimum staffing levels for registered nurses (RNs) and certified nurse assistants (aides, or CNAs) but not Licensed Professional Nurses (LPNs, or Licensed Vocational Nurses). The new rules would not set a minimum for total nursing and aide hours, which some advocates fear will result in facilities cutting LPN staff to save money rather than increasing overall time providing care.

Experts often point to a 2001 federal study that estimated the minimum level of staffing needed to limit harm from omitted and delayed care: 0.75 hours per resident from RNs, 0.5 hours from LPNs and 2.8 hours from CNAs for a total minimum of 4.1 hours. CMS considers these to be recommendations, but not rules. These calculations were based on face-to-face time with residents although staffing levels reported federally often includes nurse time spent doing administrative duties.

More recent academic research supports a need for higher levels of care than the 2001 study recommended. The figures from this more recent research were designed to be a rough guideline for how facilities could comply with the existing federal requirement for “sufficient staffing” to meet the care needs outlined in each individual’s care plan (a document required to be maintained for each resident by the Director of Nursing and other RNs).

Background reading and other resources

Before we get to the reporting recipe, here is a list of background reading and other resources you might find helpful.

-

ProPublica’s Nursing Home Inspect tool compiles inspection reports and other quality information about nursing homes, allowing you to download the PDFs or request a bulk data download.

-

Most federal data about nursing homes can be found at data.cms.gov, including the daily time card data used in this reporting recipe. Some files, however, such as those connecting particular citations to particular fines or the letters sent by CMS to facilities with care deficiencies must be requested.

-

Brown University, under contract from the National Institutes of Health, has access to patient-level records from CMS that it compiles into facility-level and state-level metrics for researchers and journalists to use. These include calculations of care needs, average age, racial demographics and other topics.

-

This slideshow from NICAR 2023 includes an extensive breakdown on the senior care industry, reporting angles, resources and example stories that were compiled by Fraser and Arizona Republic Reporter Caitlin McGlade.

-

For a general overview of staffing levels in nursing homes, read this story from USA TODAY’s Dying for Care project. The investigation detailed failures to enforce federal staffing recommendations even when there was evidence of serious injury or death. It also provides historical context about proposals for staffing levels, academic research and challenges in the oversight system. Additionally, it includes an interactive map with information about state-level staffing requirements.

-

Many states do not have enough inspectors to visit facilities for routine reviews, let alone respond to complaints that do not involve a death or require significant work to document. CMS could hold states accountable for this poor staffing and underfunding, but rarely does.

-

For a deep dive on the financial relationships between operating companies and the web of corporate owners (including real estate investments who own the physical building), read this story about one company’s COVID track record and this one for a summary of ownership records collected by regulators. Others have written about private equity in particular. The National Bureau of Economic Research linked higher mortality rates, in part, to lower staffing levels.

-

The Arizona Republic’s project, The Bitter End, has done fabulous work explaining the state of dementia care in the United States and resident-on-resident violence, including in nursing homes. Among other findings, they examine staffing levels, turnover and training. They describe their reporting in this article from the series.

How you can analyze the data

While USA TODAY has written about the scope of staffing issues and highlighted particular facilities or states, there is room for other journalists to review the trends, laws and reform efforts in their states or communities.

The data used by USA TODAY and presented here comes from CMS’ Payroll-Based Journal, which has been collected since 2017. The particular file used the hours worked on each day by RNs, LPNs, CNAs and others at every skilled nursing home in the country that accepts payment from Medicaid or Medicare.

The reporter simplified that massive file into a spreadsheet with one row for each of the roughly 14,500 nursing homes in the country with reliable data. It counts the number of days that the facility met the proposed staffing requirements, the number of days it met the 2001 recommended levels and a calculation for how much the facility fell short on an average day.

The biggest challenge reporters face in working with this data is providing appropriate context for readers about the definition of “hours per resident per day” and what it means for a facility to be above or below the various standards. In many cases, differences will equate to minutes. It also is important to remember that averages can obscure significant differences between individual days. For instance, facilities often have lower staffing on weekends than weekdays even though the care needs do not change.

Also, these figures do not take into account the specific health care needs of residents. Some people will require significantly more care time to comply with existing federal rules that require “sufficient staffing.” Some facilities will have more short-term residents and some will have more long-term residents. However, the minimum staffing proposal is exactly that: a minimum, or floor, below which researchers have found it is common for residents of any kind to experience medical delays or harm.

This data also does not provide information on ownership, inspections, complaints or state-specific requirements. Additional reporting will be beneficial, particularly when focusing on a handful of facilities rather than taking a broad view. Suggestions on these additional reporting strategies can be found in the resources linked above, among other places.

Nonetheless, it is rare for any regulator to collect daily staffing levels from establishments. It provides a unique opportunity for understanding the business decisions behind facilities that serve American residents with significant health care needs and whether public officials are sufficiently monitoring those facilities.

Three quick data notes:

-

Column A does not have a label, but is a unique ID code for each row that was generated by R upon export.

-

The ‘PROVNAME’ column, or provider name, given to CMS for official records does not always match the business name a facility uses in marketing to the public. Other times, a facility will have changed names when a new operator buys the business. Addresses and business filings with the Secretary of State can help verify.

-

The ‘ID’ column is the unique CMS ID given to each location, which can be useful for connecting multiple data sets or when reviewing other documents. It is important to note, however, that Excel automatically removes the zeros in front of some of these IDs and interprets others as large numbers, presenting those with an “E” in the middle as if scientific notation was intended. Each ID should be six characters long. If it’s shorter, there is likely a zero in front. If it’s wonky, it’s probably the scientific notation issue. If you save the CSV file after opening in Excel, these problems could remain, so be mindful if you intend to use the file in other programs, like Python or R. Experienced Excel users can avoid these issues by importing your CSV into a blank file and choosing to “Transform Data,” setting the ID column’s format to text.

Here are some initial steps to dig into the data:

The 2023 Q2 data that USA TODAY and Big Local News compiled and standardized is available for download from the Stanford Digital Repository. Download the CSV file ‘NursingHomes_staffanalysis_2023_1031.csv’.

For those who want to understand how USA TODAY converted the daily time cards into this summary file, please download the HTML file:

- ‘Rmarkdownfile_NH_staffinglevels_BIGLOCAL_2023_0931.html’

It includes the R code used for data cleaning and analysis as well as plain-language explanations of each step. This will be particularly helpful if you want to review a different time period than the second quarter of 2023 or want to adapt the code for a different analysis. It includes more discussion of data limitations and quirks.

Here are some specific steps using Excel that you can follow to answer important questions about what staffing levels look like at facilities in your community.

Do skilled nursing facilities in my town meet the staffing minimums proposed by Biden?

Open your file in Excel.

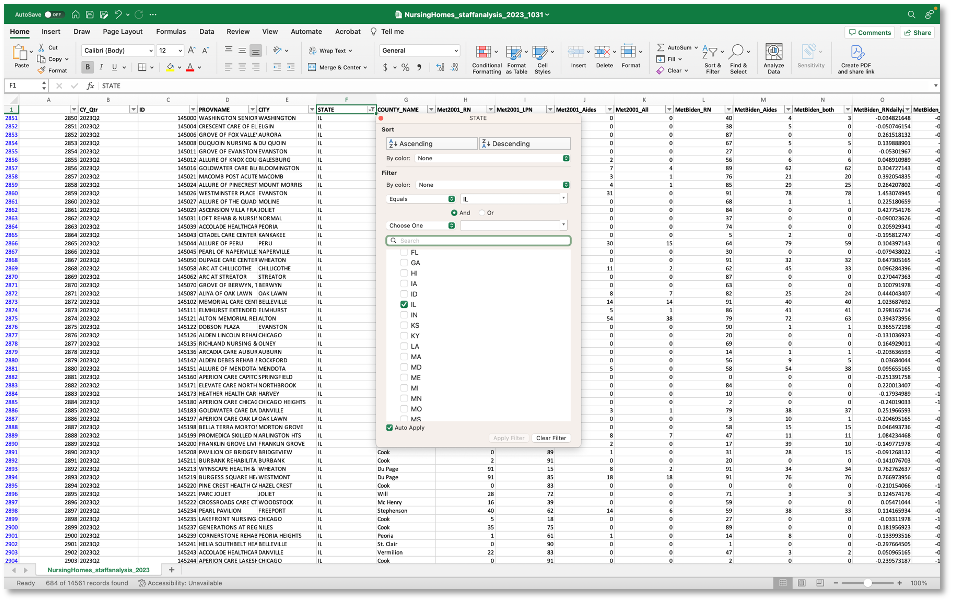

Click on ‘Data’ on the menu bar at the top of your Excel workbook, and click ‘Filter.’ This will add a button to the top right corner of each column which opens a dropdown menu of options.

Click on that dropdown menu for column F, which is labeled ‘STATE.’ Click the box next to ‘Select All’ to start with a clean slate. Then click the box next to the state where you report. Click ‘OK’ to close the dropdown menu and apply your choices to the spreadsheet. This will present you with facilities in that state only.

Repeat the filter process, if desired, to limit your choices to facilities in a particular city or with a particular name.

For this demonstration, let’s focus on Alhambra, Illinois, where two skilled nursing facilities take payments from Medicaid or Medicare. Here is a rundown of columns G through O along with an example of what I can see from the data about Alhambra Rehab & Healthcare (Column A’s unique row number for the facility is 3392).

-

H - Met2001_RN - On 83 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met the RN minimum recommended by CMS in 2001.

-

I - Met2001_LPN - On 49 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met the LPN minimum recommended by CMS in 2001.

-

J - Met2001_Aides - On 1 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met the CNA minimum recommended by CMS in 2001. (USA TODAY has previously reported that Illinois has consistently ranked as having the nation’s lowest CNA staffing levels.)

-

K - Met2001_All - On 1 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met the RN, LPN and CNA minimums recommended by CMS in 2001. Remember, researchers say that staffing less than these minimums means delayed and skipped care is likely.

-

L - MetBiden_RN - On 89 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met the RN minimum proposed by CMS this fall.

-

M - MetBiden_Aides - On 19 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met the CNA minimum proposed by CMS this fall.

-

N - MetBiden_both - On 19 of 91 days in 2023 Q2, this facility met both the RN and CNA minimums proposed by CMS this fall.

-

O - MetBiden_RNdailyavgdiff - On an average day in 2023 Q2, this facility was 0.5 hours above the RN minimum for each resident each day proposed by CMS this fall.

-

P - MetBiden_Aidesdailyavgdiff - On an average day in 2023 Q2, this facility was 0.3 hours below the CNA minimum for each resident each day proposed by CMS this fall.

How does a single facility compare to the statewide averages?

If you wanted to compare this to the statewide averages, remove the filter from the ‘CITY’ column. You can do this by clicking on the dropdown menu button for the column and clicking on ‘Clear Filter from “CITY.”’

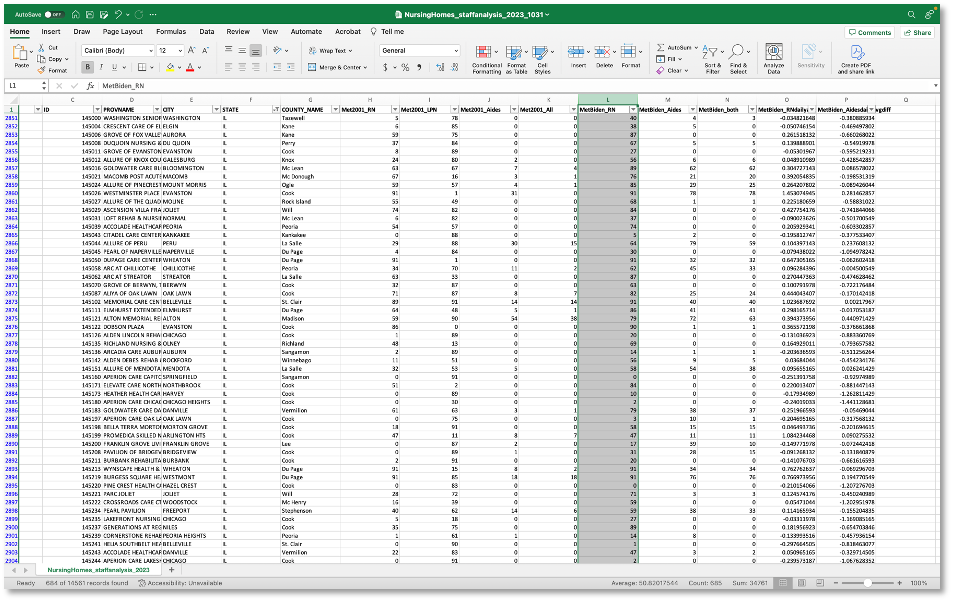

Click on the letter above a particular column of interest. Let’s start by clicking on ‘L,’ above the column heading of ‘MetBiden_RN.’ This selects the entire column, signified by highlighting it gray.

You’ll notice some numbers appear in the bottom right corner of the screen: Average, Count and Sum. These calculations are based on all the cells with values in Column L. So we can see:

-

On AVERAGE, facilities in Illinois met Biden’s proposed staffing minimum for RNs on 50.8 days out of 91 in the second quarter of 2023. Earlier, we saw that Alhambra Rehab & Healthcare met that proposed standard 89 of 91 days.

-

COUNT is, well, a count of the number of rows in the selection, which means there are 685 facilities in Illinois for which USA TODAY had reliable federal data to analyze.

-

SUM is not immediately useful in this case, but can become a useful finding with some basic math. It adds up all the numbers in column L to 34,761. Multiply the number of facilities (685) by the number of days in 2023 Q2 (91) to get 62,335 total days of care provided by Illinois nursing homes in that period. If you do some division(34,761 / 62,335), you get 0.557. That can be written as this: Illinois nursing homes fell short of Biden’s proposed minimum staffing levels for RNs on more than half of the days (56%) in the second quarter of 2023. If we convert Alhambra’s 2 days when it fell short (out of 91 days) to a percent, we get 2%. As a reporter, you might reach out to facilities closer to meeting Biden’s requirements as an example that it’s possible and to understand why they’re different from most.

How does a single facility rank compared to others in the state?

Make sure you still have a filter on Column F to keep the data focused on Illinois. No other columns should have a filter yet.

Let’s continue to work with Column L ‘MetBiden_RN.’ Click on the dropdown button and select “Sort Largest to Smallest.” This will sort the spreadsheet based on the numeric values in Column L. (If the column had been formatted as text, the options would have been to sort A to Z or Z to A instead.)

Click in the first cell below the column label ‘MetBiden_RN,’ which should have a value of 91. Without clicking in any other cell, scroll down until you see the row for Alhambra Rehab & Healthcare (which will be around row 2949, depending on if you’ve done other sorts earlier). Holding down SHIFT on your keyboard, click on the cell with the first entry of ‘89,’ which was the figure for Alhambra Rehab. (The first ‘89’ should be row 2940.) This will highlight all the cells from the first facility down to the first instance of ‘89.’

If you look in the bottom right corner, you can see the COUNT value is 99. That is the approximate ranking for Alhambra Rehab & Healthcare on this metric. You could write a sentence to the effect of: The facility ranked 99th out of Illinois’ 685 skilled nursing facilities for the number of days it met the proposed RN staffing requirements.

You also can do some basic math to help readers make sense of those two big numbers. Divide 99 by 685 to get its percentile ranking: 0.14 is 14%. (Think about standardized test scores to understand and explain percentile rankings.) You could write a sentence like this: The facility ranked in the top 14% of Illinois facilities for the number of days it met the RN minimum staffing requirement proposed by Biden. Or, subtract 14% from 100% to write this: The facility met Biden’s RN staffing proposal on more days than 86% of facilities in Illinois.

About Big Local News

From its base at Stanford University, Big Local News gathers data, builds tools and collaborates with reporters to produce journalism that makes an impact. Its website at biglocalnews.org offers a free archiving service for journalists to store and share data. Learn more by visiting our about page.